Self-Portraits of a Homeland

Dear Randa,

Thank you for all the images of your latest work. It’s very compelling. I look at it again and again. And I want to try to describe to you how I place it as a spectator in my imagination.

I return to Palestine and I look at the earth I’m walking on: its grasses, its boulders, its ditches, its tangled undergrowth, its copses, the roots of its trees, its pools, and I think that what they endure as fragments, not of the earth, but of a homeland, is expressed in the figures you create. Through you the self-portraits of these territorial particles came into being. It is as if you hold a pebble from the Golan Heights in your left hand and with your right hand draw what is inside it…

John Berger

Clay

Emanuel Swedenborg saw hell. According to him, its creator designed it in the shape of a human being and draped it in skin, its bare organs and the darkness of its bowels populated by humans. It is lived from within, a monster living in the belly of another human. We each have our own personal hell, complete with human features and characters, and distinct from the hell of the others.

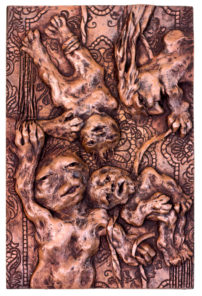

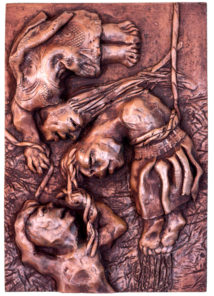

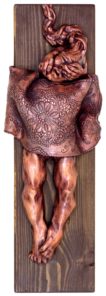

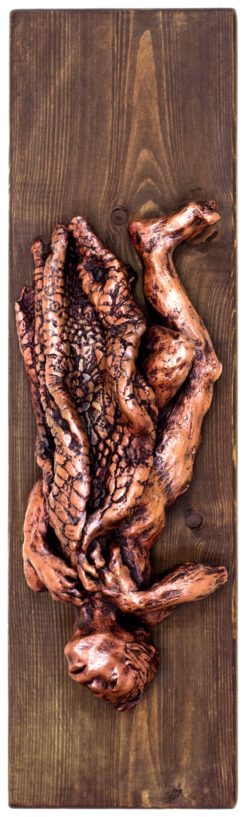

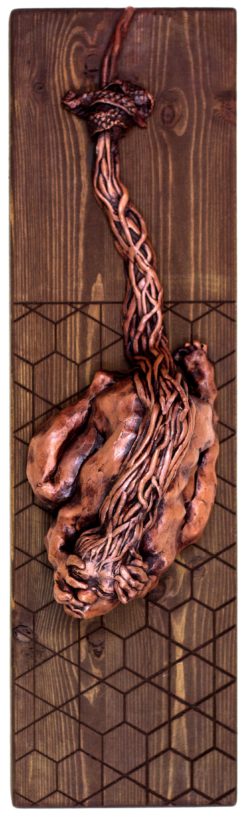

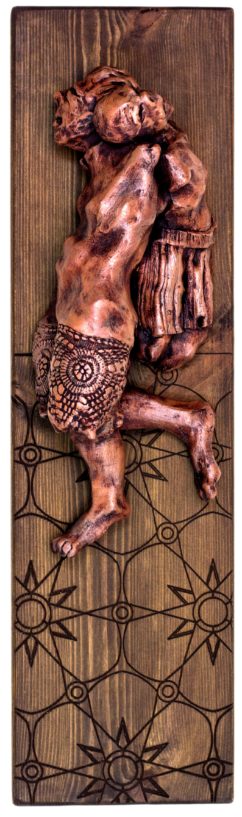

In Randa’s pencil drawings and clay and bronze sculptures, we see creatures frozen at that threshold, “petrified with pain”, as they cross or stumble in between two vast and intertwined hells. Inside the body and outside of it. Secretly coming and going. These creatures are not fleeing the hell, they are a part of it, some since their creation. They are disfigured, perhaps when extracted from the depths, or perhaps becoming so by the pain of persistence to hold on to this turmoiled existence. Their bodies were formed to be inhabited by the last of solitudes, for they accumulate the ancient solitudes and fears, and Randa reveals to us that which we don’t see. When inside the fire one does not see other fires that scorch the world around us, flames touching every single body and creating terror amongst them, burning their features and melting their parts, uniting them in this carnage. Or perhaps it separates and disperses them, with a threat of reunion. This is what fertility of death is, and the reproduction of multiple ends with one another. We perceive the sculptures as if they were born dead, or perhaps even as dead birthed by dead, imprisoned by the death of others in a nightmare that stands outside of time. Randa sculpted the moment of the falling of these creatures from towering heights as their hair rose up like flames. She captured them as they stood crucified, or as they stood pleading as little girls hold on to the skirts of their panicked mothers. As they stood chained by ropes the ends of which we do not see, pulling at wrists, ankles and necks. Perhaps these are ropes of rescue. Or ropes of gallows. Or perhaps they are ropes of swings. Or of wells where young men, strangers, have killed themselves. Or perhaps they are strings suspended from kites. Or dead braids that never stopped growing, pleated long and sturdy like nooses. We see in these unknown creatures who had been hurled from the tallest of towers, falling to their immediate death and oblivion. Or who had fallen after a shell had blown them away.

Or who had disappeared during sleep. Or who had been crushed, their features flattened out by heavy wheels of the passing time. Or those that drowned and have been exhumed like vessels from old sunken ships. And how cruel are the saviours when they pull the drowned by his hair, then left to die lying before the eyes of the living ones.

Here in this exhibition, after the fingers get lost in the clay, we will think of what is left behind the fires and the pain. How dying is like dancing. Pain carves features, and it encourages the creation of flying and clowns. It shuts the eyes that haven’t been swathed in fear. Before us, in these faces, different times and ages merge into each other, childhood mingles with old age, tenderness with illness. Severed noses, and mouths gaped open even after the screams, which we don’t hear, have stopped.

Fates are to be lived and not to be interpreted. The audience to the Syrian pain has scattered, and the torture has continued and souls have patiently been baring that which is unbearable. The hand of the sculptor liberates the dead, and so we see an old wound of the prime formulating material: what the fingers had seen inside a vortex of images concealed inside the clay, touched by our eyes after the figures emerge from the fire. The sculptures had been baked, Syria had been slaughtered. The hopeless plead for the horizon to split with the blood of its dead. Perhaps the hands will create a new life from the soil of this tremendous pain. Perhaps they will recover, in the cycle of birth and death, the dawn of creation told to us by the myths: the day of the slaughtering of the great ram, its blood kneaded with the crust of the soil to create the first human. Weddings in the Levant return to this ritual, when the hands of the bride are painted with henna as if it’s the first clay kneaded with blood. As if there is a birth awaited by the waiting ones, and the confused and the tortured, their pleas fastened to the power of life that binds itself to the death and lives with it.

Golan Haji Paris, 2016

Golan Haji is a Syrian Kurdish poet and translator. He lives in France.